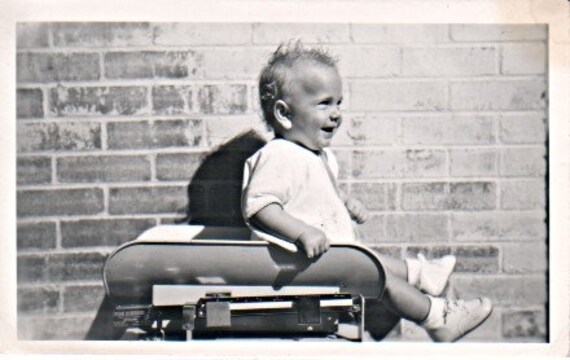

Once upon a time, there was a German couple who immigrated to Missouri and started a farm. Even though the country where they came from did not allow slaves, the couple decided to buy a few slaves to help them run the farm. Maybe the couple made a pact to always be kind to their slaves. Or maybe they simply and unexpectedly found their slaves worth loving.

Either way, when in 1864 night raiders captured their slave Mary and her baby, the couple traded their only horse to pay a man to bring them back.

|

| Have horse, will trade for baby. Hmm. |

The man came back with a week-old baby, Mary's frail son.

Mary was never seen again.

The couple, Moses and Susan Carver, decided to raise the baby. They named him George.

This was just at the tail-end of the Civil War. Slavery was abolished, but the former slaves had few rights or privileges. For one thing, they couldn't go to school.

And George really wanted to go to school.

“Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom.”

Susan taught him to read and write, and from there George learned everything he could from anyone he could. As he grew older, he moved from town to town doing manual labor and searching for knowledge. This search eventually got him accepted to a college - which immediately sent him away when he showed up and wasn't what they wanted.

But eventually he got to Iowa State Agricultural College where he achieved a BS and then a master's in botany. After that, he stayed on to conduct research at Iowa Experiment Station. His work in plant pathology (disease) and mycology (fungi) gained him national recognition as a respected botanist.

“When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.”

Iowa State wanted to keep him, and hug him, and call him George. They offered George money, research assistants, and a cushy position. Beautiful end to a sad story, right?

Nope.

That's when Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, heard about him. Washington desperately needed qualified teachers. He didn't think that such a distinguished person would want to work for him, but since it never hurts to ask, he sent George a long letter, telling him all about the things the southerners were suffering through, all the problems that were cropping up in their society.

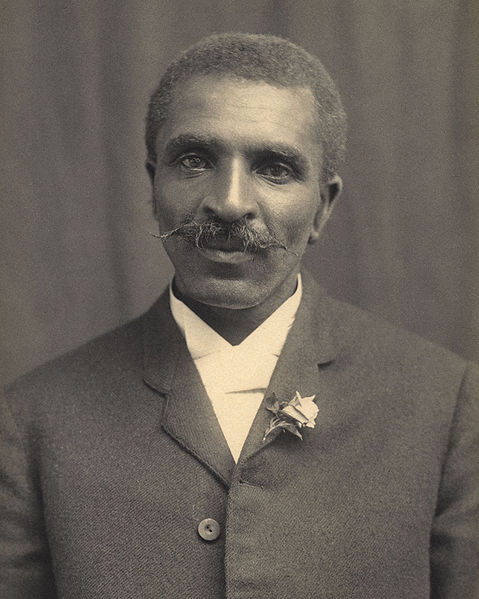

|

| Carver in 1910 |

|

According to rumor, George sent back a telegram that contained only two words.

"I'm coming."

George spent the rest of his life figuring out ways to improve life for people. He created paints out of local clays so that people could paint their houses and churches. He made an oil to treat infantile paralysis and one day every week, mothers would line up and hand him their babies to have life massaged into them. He taught farmers about crop rotation so the soil wouldn't be depleted. Most famously, he came up with around 300 uses for the peanut.

To me, George Washington Carver was not great because of his science, although he was an incredible scientist. Carver was great because he loved people. He used his skills, studies and research to help people.

“Anything will give up its secrets if you love it enough. Not only have I

found that when I talk to the little flower or to the little peanut

they will give up their secrets, but I have found that when I silently

commune with people they give up their secrets also – if you love them

enough.”

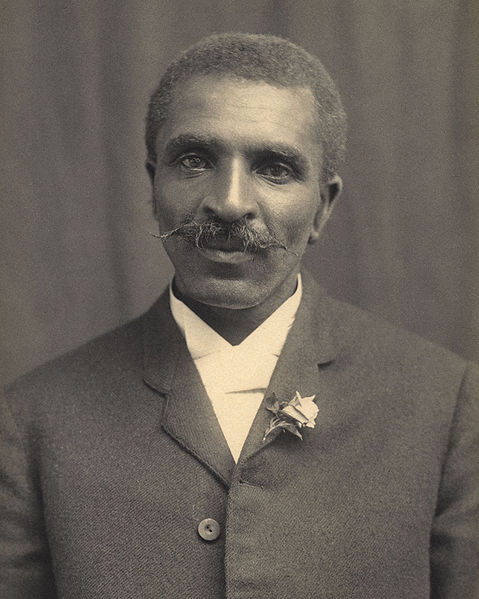

|

| Carver working in his laboratory. |

|

One funny thing about Carver - when he came to the Tuskegee Institute, he was wearing a suit. He wore that same suit the rest of his life, keeping it clean and pressed and mended. He never wanted another one. Carver only picked up his paychecks when he needed money, and he rarely needed money. When he was in his 70s, he finally picked up all his paychecks and used the $60,000 (the equivalent of around $777,000 today) to create a research fund.

This man was a truth-seeker, someone who lived with passion and delighted in everyday adventure.

I want to live like he did.

(Quotes in italics are by George Washington Carver.)